Alpujarra walks

Number One: Mulhacén

From Capileira, last village on the road to Sierra Nevada National Park, the number one hike has to be Mulhacén mountain, which at 3,479 metres is the highest in mainland Spain. It presents a not-so-difficult challenge except in winter, when snows may be too deep.

From Capileira, last village on the road to Sierra Nevada National Park, the number one hike has to be Mulhacén mountain, which at 3,479 metres is the highest in mainland Spain. It presents a not-so-difficult challenge except in winter, when snows may be too deep.

|

Mulhacén

From Paraje del Cascacar to Mulhacén summit: 2 hrs 30 mins From Mulhacén summit to Refugio Poqueira: 3 hrs From Refugio Poqueira to Paraje del Cascacar: 1 hr 15 mins Difficulty: Medium-to-difficult Plan your stay When's the best time of year to come? Find out the answers to FAQs on Alpujarras holidays. Before you come, we can also put you in touch with the most experienced, knowledgeable walking guides in La Alpujarra. |

This itinerary was left by a zigzag wanderer who hadn’t climbed Mulhacén for 20 years, for a future self who might yet have the legs though not the memory to find his way. Let it serve you, gentle reader, as a portal to high mountains that will test, refresh and make you feel alive.

Remember to take, like the wanderer, water and a bite to eat, a hat, sunglasses and sun protection, a charged mobile, a special friend, a pipe, harmonica or similar personal whim, layers of clothes against the cold, comfortable boots, and love in your heart.

It was summer in Capileira and the Sierra Nevada minibus was already running people up into the mountains. After a leisurely Andalucian breakfast at the Moraima of toast smeared with garlic, tomato and olive oil, he boarded across the road at the Information Kiosk, where he had previously booked a ticket, leant back and let the 11 o´clock bus take the strain.

Remember to take, like the wanderer, water and a bite to eat, a hat, sunglasses and sun protection, a charged mobile, a special friend, a pipe, harmonica or similar personal whim, layers of clothes against the cold, comfortable boots, and love in your heart.

It was summer in Capileira and the Sierra Nevada minibus was already running people up into the mountains. After a leisurely Andalucian breakfast at the Moraima of toast smeared with garlic, tomato and olive oil, he boarded across the road at the Information Kiosk, where he had previously booked a ticket, leant back and let the 11 o´clock bus take the strain.

Sierra Nevada Information & Bus service, Capileira

Tel: (+34) 671 564 406 & (+34) 958 76 30 90

Email: [email protected]

Advance booking & payment for the National Park bus is essential. In summer, weekend buses tend to be booked up completely 2 weeks in advance.

The bus runs on most days during the summer months, plus some weekends in spring and autumn.

Tel: (+34) 671 564 406 & (+34) 958 76 30 90

Email: [email protected]

Advance booking & payment for the National Park bus is essential. In summer, weekend buses tend to be booked up completely 2 weeks in advance.

The bus runs on most days during the summer months, plus some weekends in spring and autumn.

The road winds up above Capileira for 13 km, eventually reaching an area of pine trees at the entrance to the National Park at Hoya del Portillo*, where other visitors leave their cars, for from here they must continue on foot. The bus, however, is the one passenger vehicle permitted to enter. There’s no one on the gate to open the barrier across the road, but no matter, the barrier’s not locked. The driver gets out and strolls over to lift it up out of the way so that he can drive through.

The National Park bus

The National Park bus

*Important update: As of summer 2019, the bus is only permitted to go as far as the Paraje del Cascacar at 2,600 m, from where you would start the hike described here by walking up to the Alto del Chorrillo at 2,700 m.

The bus goes up past the Mirador de Trevélez and the last stunted or wind-broken pines into a terrain of rock, the habitation of longbacked black beetles, tiny flowers and, he knew, families of ibex.

He stepped out of the bus at its highest limit before Mulhacén and looked around in a blustery midday.

The bus goes up past the Mirador de Trevélez and the last stunted or wind-broken pines into a terrain of rock, the habitation of longbacked black beetles, tiny flowers and, he knew, families of ibex.

He stepped out of the bus at its highest limit before Mulhacén and looked around in a blustery midday.

|

One was a steepish dedicated biking track, down which a lone two-wheeler descended rapidly and passed the hikers with a smile of pleasure on his face.

|

A wide track to the left went 3.5 km down to the Refugio de Poqueira, which is where the wanderer planned to stay the night.

This would be his return route the following morning. |

But our wanderer’s sight was set on a thin path that drew a wavering line up towards the round Christmas pudding of Mulhacén, complete with icing sugar, that rose ahead of them.

|

The wind warned him it wasn’t going to make it easy and he set off with his hoody up and sunglasses on to ward off the high sun and the blowiness. Onwards then, taking the place in.

The way up this southern flank is a simple slog. From el Alto del Chorrillo at 2,700 metres to the summit at 3,479 metres the approach is neither steep nor technically challenging. The terrain of grey slate is featureless and bleak, so much so that the hike presents itself as an almost dreary, dutiful prospect, one that the wanderer expects to have the stamina to manage without hopes of excitement.

But for the damn wind, it might have been so. As he was boxed around the face and ears, pushed around and hindered by the stiff winds, the way became anything but straightforward. Occasionally it was sideways when the gusts caught him unawares. The nameless wanderer could hardly have been more anonymous with the hood of his jacket tied tightly under his chin and the rest of his visage masked by wraparound sunglasses. His eyes fixed on the next step ahead, boots dislodging loose stones, he pressed onward and upward, shoving hands numbed by the cold air into pockets, mindful less of the story of Muley Hacén, whose name the mountain bears, than of Wilbur Mercer the quasi-religious figure in “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”, who struggles time and again, to ascend a steep hill, while non-believers throw rocks at him.

The way up this southern flank is a simple slog. From el Alto del Chorrillo at 2,700 metres to the summit at 3,479 metres the approach is neither steep nor technically challenging. The terrain of grey slate is featureless and bleak, so much so that the hike presents itself as an almost dreary, dutiful prospect, one that the wanderer expects to have the stamina to manage without hopes of excitement.

But for the damn wind, it might have been so. As he was boxed around the face and ears, pushed around and hindered by the stiff winds, the way became anything but straightforward. Occasionally it was sideways when the gusts caught him unawares. The nameless wanderer could hardly have been more anonymous with the hood of his jacket tied tightly under his chin and the rest of his visage masked by wraparound sunglasses. His eyes fixed on the next step ahead, boots dislodging loose stones, he pressed onward and upward, shoving hands numbed by the cold air into pockets, mindful less of the story of Muley Hacén, whose name the mountain bears, than of Wilbur Mercer the quasi-religious figure in “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”, who struggles time and again, to ascend a steep hill, while non-believers throw rocks at him.

Muley Hacén

Mulhacén, at 3,479 m the highest mountain in the Iberian peninsular and the 64th highest in the world, is named after the Muslim ruler Abu l-Hasan Ali, Sultan of Granada, who was known to his Christian adversaries as Muley Hacén. His unwise invasion of Zahara de la Sierra led to a 10-year campaign by the Catholic Queen Isabel of Castile and King Ferdinand of Aragon to conquer his capital of Granada. It was by then in the hands of his son, Abu ‘Abd Allah Muhammed XII, known as Boabdil, who surrendered Granada in 1492, along with its Alhambra stronghold and palaces, thus marking the culmination of the Christian reconquest after over 700 years of Muslim rule in Al Andalus. Legend has it that, Zorayda, Abu l-Hasan’s wife, a former Christian slave with whom he fell in love, complied with his last wish to be buried on the mountain, which would thereafter be named after him.

Mulhacén, at 3,479 m the highest mountain in the Iberian peninsular and the 64th highest in the world, is named after the Muslim ruler Abu l-Hasan Ali, Sultan of Granada, who was known to his Christian adversaries as Muley Hacén. His unwise invasion of Zahara de la Sierra led to a 10-year campaign by the Catholic Queen Isabel of Castile and King Ferdinand of Aragon to conquer his capital of Granada. It was by then in the hands of his son, Abu ‘Abd Allah Muhammed XII, known as Boabdil, who surrendered Granada in 1492, along with its Alhambra stronghold and palaces, thus marking the culmination of the Christian reconquest after over 700 years of Muslim rule in Al Andalus. Legend has it that, Zorayda, Abu l-Hasan’s wife, a former Christian slave with whom he fell in love, complied with his last wish to be buried on the mountain, which would thereafter be named after him.

Wilbur Mercer

In Phlip K. Dick's novel, "Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?", on which the movie "Bladerunner" was based, people using an Empathy Box plugged in at their homes feel not only Wilbur Mercer's weariness but also the physical pain when stones strike him. The empathic solidarity that this creates in followers is what underlies the religion of Mercerism. Mercer is later revealed to be a retired bit actor.

In Phlip K. Dick's novel, "Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?", on which the movie "Bladerunner" was based, people using an Empathy Box plugged in at their homes feel not only Wilbur Mercer's weariness but also the physical pain when stones strike him. The empathic solidarity that this creates in followers is what underlies the religion of Mercerism. Mercer is later revealed to be a retired bit actor.

With brief stops to examine the tiny flowers that cling to the mountainside – and not at all to rest, because he’s feeling knackered already, no, gentle reader, just for the flowers – he makes progress.

Fortified by boiled sweets, desire and the knowledge that a thousand grannies have made it here before him, he presses onward and upward. And of course the top of the pudding isn’t the summit, the brow of the great mountain dome he had seen from below isn’t the summit, there’s another craggy height to reach and that’s not it either. But final stretch does then come and is there for the taking, the summit in clear sight.

He gets there, twirls around, resists the vertigo atop the last concrete slab and takes a look all the way around.

He gets there, twirls around, resists the vertigo atop the last concrete slab and takes a look all the way around.

Video of the panorama from the top. Don't miss the ibex and bald head.

Just below, an ibex and there another, has approached, attracted by the generous energy of the victor or, just perhaps, the remnants of the picnic that they know he will now want. When he does sit for a sandwich and a biscuit, in the shelter of a stone bivouac, swirling around in the stiff wind like tiny scraps of paper are orange-winged butterflies. They hurl themselves away with the wind or come to rest on the ground in front of him, where they take the sun. Butterflies are his particular companion, his animal guide. The reassurance they give him raises his spirits so nicely that he toots a little tune on the harmonica. They tell him it is time to go, to find the other way down. To the refuge, to the refuge… the Refugio Poqueira mountain shelter, where he had reserved a bed for the night and dinner to boot.

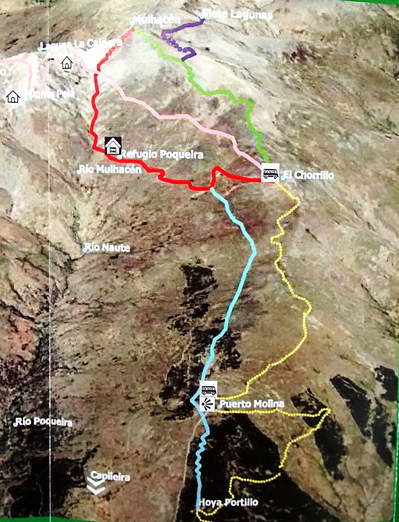

Green route up, red route back

Green route up, red route back

He could return the same way, down the southern flank to Alto del Chorrillo at 2.700 m, and then walk the last 3.5 km to the Refugio at 2.500 m, but the wanderer likes his wandering and he will take the alternative route down the western face and the follow the River Mulhacén as far as the Refugio.

He stretches up again into the sun and looks around where he has been sitting, for nothing can be left behind in the National Park, not even the crumbs of a sandwich.

The path down the western face is not easy to find to begin with and he ends up clambering down over the rocks before spotting and joining the narrow, less trodden path of shale that shifted underfoot, and thus begins a painstaking way down.

In this powerful landscape, desolate in its absence of colour and life beneath a strong, blue sky, the outstanding feature is the Laguna de la Caldera:

The vast “cauldron” is a frozen lake fed by melting snows, and the cirque it occupies is gouged out of the mountainside at three thousand metres. Beside it there stands a simple stone shelter, where it is possible to camp. Our wanderer, however, is already dreaming of a hot shower and a comfortable bed. One uncertain step at a time, our wanderer edges down, zig zag zig zag.

|

At the foot of the twisting path, a broad track leads right to the Laguna or left to Alto del Chorrillo.

The narrow path to the Refugio crosses this track and continues downwards to a river bed, and it is indicated again by a series of cairns. The Refugio is not signposted, since the National Park authority resists any such manmade intrusions. There may, though, be a metal sign at the crossing prohibiting bicycles, as a clue to being on the right track. |

A long winter, full of rain, is to thank for the long patch of luminescent green which stretches out along the river bed below. When he reaches it, he is delighted to find an adult male cabra montesa (ibex) grazing on peat moss, the source of the effulgent green, through which cut a tiny rivulet, making a groove in the cropped vegetation and the snow, which still in summer lay in broad lozenges for a long way down the gorge.

The path, faithfully marked by the unlit beacons of the cairns, descends the gorge to the left of the little river’s clear, running water, which pools in places spreading greenness at either side. The disconnection from other humans and their habitation expands awareness and advises caution. There are no power lines, no tracks other than a boot print, just nature in its natural wildness.

The descent is hard on the knees and he has sometimes to stamp through bank of packed snow, tinged a rusty red from the dirt of its frozen assets. Not even banks last forever, though, and here the natural persistence of running water bore a hole right though one:

The descent is hard on the knees and he has sometimes to stamp through bank of packed snow, tinged a rusty red from the dirt of its frozen assets. Not even banks last forever, though, and here the natural persistence of running water bore a hole right though one:

After two hours, the rivulet has grown in size and force, owing to an array of streams that join it along its course, to become a small but lively river: the River Mulhacén, no less. The wanderer, aware of deepening shadows, rounds a ridge to a more open view down the gorge. The mountain refuge is nowhere to be seen. The sun is getting low, he has little water left, and the night here will freeze.

Ah, but what a song of love in the heart can do! That and the prospect of a cold beer and a hot dinner. The wanderer continues his clamber down.

|

He advances with the familar grogginess of the walker, with only an an occasioanl butterfly from the guild of guides to focus him. One, a diminutive black-and-white creature, suggests a chequered flag; the other, also tiny, but brightly mauve, is familiar to him from lower altitudes and home at the cottage. A half hour later, he sees how the path ahead diverges at last from the river to snake uphill to a low ridge. It is marked by the cairns and also by orange poles stuck into the ground. |

|

The river has grown from a rill to a lively tumbling flow and as he walks up and away from it, the mountain peacefulness returns to his ears. Not long after passing the ridge, a last corner is turned and the Refugio comes into sight. Standing not far off, it is a far more impressive and sturdily built edifice than he had imagined, set in beautiful isolation. |

Refugio Poqueira

at 2.500 metres

Open 365 days a year

Information & bookings:

Web: www.refugiopoqueira.com

Tel: (+34) 958 34 33 49

The Poqueira mountain refuge has been open since 1997 and the very hospitable Rafa and Ansi have honed their operation to a perfect simplicity. They know what people want and need and provide it all with admirable efficiency and courteous warmth.

Accommodation, in bunk beds in shared dormitories or private rooms, thoroughly satisfying four-course lunches or dinners, cold beers, water, tokens for hot showers and the hire of just about any item imaginable, from sheets and towels to obscure climbing equipment, are neatly put on a computerized tab. All at very reasonable prices. The place is warm, dry and welcoming and the mattresses are clean and comfortable. There is no TV or radio TV in the Common Room, just a screen forecasting weather conditions. Meals are taken together at long bench tables and people sit around chatting or playing cards, while they charge devices or use the free WiFi.

The Refugio Poqueira provides this service every day of the year.

at 2.500 metres

Open 365 days a year

Information & bookings:

Web: www.refugiopoqueira.com

Tel: (+34) 958 34 33 49

The Poqueira mountain refuge has been open since 1997 and the very hospitable Rafa and Ansi have honed their operation to a perfect simplicity. They know what people want and need and provide it all with admirable efficiency and courteous warmth.

Accommodation, in bunk beds in shared dormitories or private rooms, thoroughly satisfying four-course lunches or dinners, cold beers, water, tokens for hot showers and the hire of just about any item imaginable, from sheets and towels to obscure climbing equipment, are neatly put on a computerized tab. All at very reasonable prices. The place is warm, dry and welcoming and the mattresses are clean and comfortable. There is no TV or radio TV in the Common Room, just a screen forecasting weather conditions. Meals are taken together at long bench tables and people sit around chatting or playing cards, while they charge devices or use the free WiFi.

The Refugio Poqueira provides this service every day of the year.

Once inside, he is glad to liberate his feet and swap his boots for free use of a pair of plastic clogs, before entering the great common room that serves as dining room and reception. Whether it was the good vibe, the handsomely filling dinner, the beer, the relief, or the Ibuprofen he took before lights out at 10 pm, the wanderer slept blessedly and, a generous buffet breakfast later, he was out of the door and on the last stage of his trek. Before he had gone far, he turned to take leave of the refugio.

|

From the Refugio back to Alto del Chorrillo takes 45 minutes or a leisurely one hour. From here it's 20-30 minutes back down to El Paraje del Cascacar for the bus back. A wide track offers a gentle gradient and its flattened surface makes the going easier for feet and ankles challenged by the angular rocks of the previous day. |

|

When he sat on the dusty ground to wait for the 12.15 bus to return him to Capileira, the wanderer saw three eagles soaring with the air currents. Like many a soul who has spent even a short time up in the mountain wilds, he felt a reluctance to return to a village of even five hundred folk with its noises and vehicles.

As he walked the quiet, winding streets of Capileira that afternoon, one of the orange butterflies appeared, come to signal an end or a continuity to his Mulhacén experience, so ordinary and extraordinary, so possible and reviving that he felt his whole self had been reset. He was ready to zig and zag some more. |

|

Back to: Alpujarra Walks